Opinion: A new tool in the fight to save the planet? A 6th-century Roman doctrine.

This piece was originally published in The Washington Post September 1, 2023

BY BINA VENKATARAMAN and Amanda Shendruk

A decade ago, the idea of young people suing their governments for failing to act on climate change seemed naive. How would they prove in court that planetary warming was harming them or would harm them in the future? Even if they did, could they show that forcing one state to curb greenhouse gas pollution would spare them harm from global climate change?

And there was another, more fundamental question: Does government approval of fossil fuel projects abridge young people’s constitutional rights — whether to life, liberty and happiness or to a healthy environment? Especially in the United States, the notion that teenagers might ever win such cases seemed a pipe dream.

A Montana court decision has suddenly made it a reality.

The unprecedented ruling for Montana youths ages 5 to 22 — including a rancher’s daughter, a fly fisherman, hunters and a Salish woman whose tribal land is threatened by wildfire — must survive an appeal to the state Supreme Court. But already it gives weight to an aspiration of young people worldwide to use the courts to force governments to address climate change.

The ruling would do away with a provision in the Montana Environmental Policy Act that forbids state agencies from considering the climate when greenlighting new fossil fuel projects such as coal mines. The ruling is based on the rights of residents alive today, and of those yet to be born, to a clean and healthy environment.

If judges elsewhere adopt the Montana judge’s reasoning, citizens could force lawmakers to finally enact better climate policy. And if this becomes a significant trend, future generations might exert greater power over political decisions of all kinds.

This might be a long shot. But many democracies do, in theory, guarantee their citizens the right to clean air, water, farmland, forests and other natural resources. The idea of getting judges to enforce this guarantee in more places is not unreasonable. Governments would merely be held to promises they’ve already made. The Montana ruling, for instance, rests on an explicit promise in the state’s constitution.

“The state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations.”

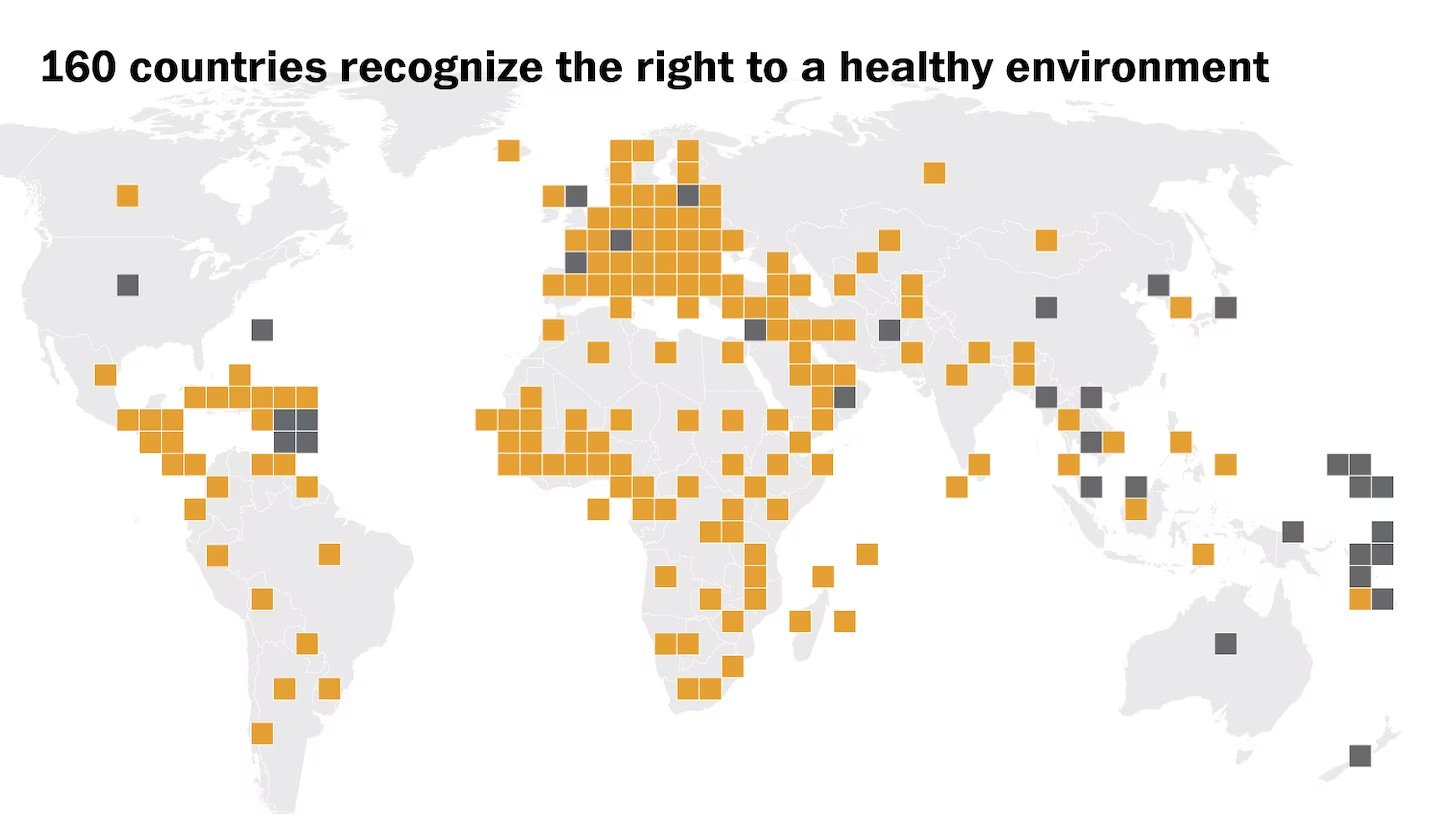

This right is widely acknowledged around the world. Similar language occurs in the national constitutions and policies of 160 countries. In some instances, it is guaranteed in international treaties the governments have signed.

Each square is one of the 193 United Nations member countries. Yellow indicates the right is guaranteed by constitution, laws or international treaties. Gray indicates it is not a guaranteed right. In the United States, the right is guaranteed by some states but not nationally recognized. Many small island nations who are the least responsible for but most effected by climate change also do not guarantee this right. Countries not labeled on the map that do not recognize the right include Afghanistan, Andorra, Bahamas, Barbados, Brunei, Cambodia, Dominica, Grenada, Kiribati, Laos, Lithuania, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Myanmar, Nauru, North Korea, Oman, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, San Marino, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. Sources: David Boyd, the U.N. envoy on human rights and the environment; U.N. Human Rights Council

Many states have enshrined similar rights. The constitutions of Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Hawaii and New York contain their own versions of Montana’s language. Florida’s constitution guarantees the right to “clean and healthy waters.” Virginia’s, like many others, requires that natural resources be preserved for its citizens. And movements are afoot in several other states to establish similar guarantees.

And beyond such explicit constitutional provisions, the ideas upheld in the Montana ruling echo across geographies and time. The idea that present and future generations have a right to a healthy and safe environment dates to 6th-century Rome. The public trust doctrine, articulated by Emperor Justinian I, implies that governments must act as trustees of vital natural resources, protecting them on behalf of future generations.

“By the law of nature these things are common to all mankind, the air, running water, the sea and consequently the shores of the sea.”

Variants of this doctrine appear in the Magna Carta, in U.S. case law and in other legal decisions worldwide. Citizens and judges can and should use it as the basis for lawsuits to compel their governments to aggressively cut fossil fuel emissions or prevent new polluting projects, says Mary Christina Wood, a legal scholar at the University of Oregon and the author of “Nature’s Trust: Environmental Law for a New Ecological Age.”

This is not to say lawsuits are the best way to make policy. In an ideal world, elected officials would act with sufficient speed and ambition to cut emissions and prevent climate disasters. But in many democracies, notably the United States, public support for climate protection is far more advanced than political action. This is primarily because the fossil fuel industry has lobbied aggressively and employed disinformation and campaign financing strategies to keep climate policies from passing. Courts, while hardly free from partisan interests, are not as vulnerable to industry influence.

By recognizing the rights of future generations, courts might even spur better policy on a range of long-term issues, not just climate but also education, genetic engineering, nuclear waste and artificial intelligence.

“The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come.”

Recent court decisions in the Netherlands, Pakistan and Colombia have also asserted the rights of young people and future generations to a safe planet. And the concept will soon be tested again in the United States. In a case set for trial next year, young climate activists in Hawaii are pushing to make their state’s transportation investments more climate-friendly. And a 2015 case against the U.S. federal government, also brought by young activists, was approved in June for trial.

“All persons have the right to: [...] Peace, calmness, the enjoyment of leisure and free time, as well as the right to enjoy a balanced and adequate environment for the development of their lives.”

This summer, it has become easier to imagine a future of deadly heat waves, devastating wildfires, warming seas and destructive storms. Climate tipping points are fast approaching, and the race is on to prevent irreversible damage.

It’s also worth imagining a time when people might finally persuade their governments to curb greenhouse gas emissions to protect people from floods and fires, as well as provide them safe air to breathe and water to drink. This future has just become a little more possible.

Bina Venkataraman is The Post’s columnist covering the future. She was previously editorial page editor of the Boston Globe, and since 2011 has taught at MIT. She is the author of "The Optimist’s Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age." Twitter

Amanda Shendruk is a visual opinions journalist. She explores creative ways to explain ideas, and uses code, data and graphics in her reporting. Twitter